Broken Chain

How the White and Indian Worlds Remembered Henry Hudson and the Dutch

Part 3 of 3

Go to: Part 1 - Part 2 - Part 3

[Full story, with Endnotes & Bibliography, also available as a PDF download]

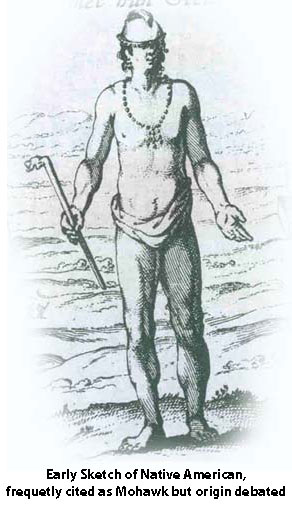

THE SACHEMS OF THE FIVE NATIONS, the Iroquois Confederacy, had come to the New York governor with many presents. On the first day of the conference, May 26, 1691, they offered three fathom of wampum, a half dozen beaver and otter pelts and a pouch of porcupine quills with which they adorned themselves when they went to war. A week later, they opened a second address with a gift of four otters. “We have been informed by our Forefathers that in former times a Ship arrived here in this country, which was a great admiration to us,” the speaker said. “Especially our desire was to know what was within her Belly. In that Ship were Christians, amongst the rest one Jaques with whom we made a Covenant of friendship, which covenant has since been tied together with a chaine and always ever since kept inviolable by the Brethren [white men] and us, in which Covenant it was agreed that whoever should hurt or prejudice the one should be guilty of injuring all, all of us being comprehended in one common League.”

So the memory of Jacques Eelkens had been handed down for three-quarters of a century. No wonder, the Mohawks’ meeting with the Dutchman left in command of Fort Nassau in 1615 was an important event. For five years, the Dutch had been trading on the Hudson, but the Mohawks had failed to make contact. Certainly, they knew the value of the goods the Europeans could bring. They had learned it from the French along the St. Lawrence. But the French had sided with their enemies, the Algonquin tribes living in the north, and together these allies had warred against the Mohawks. Now here was another white man eager to buy pelts. The Mohawks controlled rich furring areas to the west where they made their homes along the Mohawk River. They could bring canoe-loads downstream, to the great falls that tumbled over the precipice just before the confluence with the Hudson. From there, they could portage over to another stream, Tawalsantha, later to be known as Nordman’s Kill, which led to the fort the newcomers had built.

So the memory of Jacques Eelkens had been handed down for three-quarters of a century. No wonder, the Mohawks’ meeting with the Dutchman left in command of Fort Nassau in 1615 was an important event. For five years, the Dutch had been trading on the Hudson, but the Mohawks had failed to make contact. Certainly, they knew the value of the goods the Europeans could bring. They had learned it from the French along the St. Lawrence. But the French had sided with their enemies, the Algonquin tribes living in the north, and together these allies had warred against the Mohawks. Now here was another white man eager to buy pelts. The Mohawks controlled rich furring areas to the west where they made their homes along the Mohawk River. They could bring canoe-loads downstream, to the great falls that tumbled over the precipice just before the confluence with the Hudson. From there, they could portage over to another stream, Tawalsantha, later to be known as Nordman’s Kill, which led to the fort the newcomers had built.

The journey required them to encroach on the territory of the Mohicans, but they were willing to take that chance. Admittedly, the Mohicans and their allies were a ferocious enemy. Not two decades past, the wars had reduced the Mohawks so low that scarcely any of them were left on the earth. Though they had recovered, increasing their numbers like a noble germ and conquering their enemies, they could not maintain their victory. The Mohicans had prevailed again in recent years, once more rendering the Mohawks almost extinct.

But now the tribes were at peace, if only because the Mohawks avoided their enemy rather than friendship. They were eager to exchange furs for the iron implements and other materials the whites promised, and they were willing to fight for the right. For a lifetime now, the Five Nations had been Aquanoshioni, “one house, one family,” ever since the Mohawk chief Thannawage had united his people with the Oneidas, Onondagoes, Cayugas and Senecas, and given his tribe the role of eldest brother. Did that not make them strong? And did they not call themselves Ongwe-honwe, “men surpassing all others, superior to the rest of mankind?” Had they not eaten up a whole body of the French king’s soldiers, the flesh flavored like bear meat?

So the Mohawks came to find out what the Ship’s Belly held.

The Mohicans didn’t like the intrusion for they had long guarded their borders jealously. The tensions escalated almost immediately. But the Mohawks kept coming. Encouraged by the Dutch, they felt free to act belligerently, to disrupt the traffic of the Mohican allies who brought furs from the north, to congregate around the Dutch fort on the west side of the river and to push the Mohicans to the eastern shore, skirmishing with their enemy if necessary. Encountering little resistance, they increased the pressure, beating the Mohicans in fair battle until that enemy was forced to become a woman to avoid total ruin.

And with furs, persuasion and belligerence, the Mohawks enlisted the support of the Dutch. The white men coveted the pelts the Mohawks brought from the vast inland lakes, but they could not lose the support of the Mohicans. So they were willing participants when the Mohawks orchestrated their plot. Sganarady, an old Mohawk, recalled his grandfather saying he had attended the gathering and how the Mohawks were the ones to make it happen. They met on the banks of Nordman’s Kill. There the covenant of friendship was established between the Dutch, the Mohawks and the woman who the Mohicans had become.

THE COVENANT CHAIN HELD STRONG FOR TEN YEARS. But the situation was one of tolerance, not peace, no matter the friendship professed. The three parties holding the ends and the middle not only told different stories of how the Covenant Chain was forged. Their interests diverged as well. Catalina Trico might recall a time of peace, quiet and all the freedom imaginable, but beneath the surface, trouble was brewing.

The Dutch were not long satisfied with the land the Mohicans granted for their settlement of Fort Orange. Now headed by Daniel van Krieckebeeck, hailed as Beeck, the community asked the Mohicans for more in 1625. The Mohicans resisted, probably resentful of how the Dutch welcomed the Mohawks in and around Fort Orange. By now, the Mohicans themselves had all moved their homes across the river. The Mohawks were no happier with their lot. Too many Mohican allies from the north were carrying furs to the Dutch. The Mohawks’ interference with that trade aggravated the tensions with the Dutch and the Mohicans.

The first trouble started in 1625 away from Fort Orange. The Mohicans ventured up the Mohawk River to attack a Mohawk village just across the boundary between the two tribes. They drove the villagers away.

Emboldened and with war flaring, the Mohicans decided on another attack in the summer of 1626. They asked Beeck to help them, and he agreed, perhaps hopeful of receiving more land if he curried favor, and eager to punish the Mohawks for interfering with trade from the north, and confident Dutch guns would prevail. Beeck and six of his men set out with the Mohicans. A league from Fort Orange, they met the Mohawks – and disaster. The enemy flew boldly upon them with a discharge of arrows. The Dutchmen and the Mohicans turned to flee. Many Mohicans were killed. So were Beeck and three other Dutchmen. The Mohawks were brutal. They devoured one of the dead Dutchmen, Tymen Bousensz. They burned the others, except for a leg and an arm they carried home to divide among their families as a sign of their victory.

For the Dutch, the defeat was a serious setback. The new Director in Manhattan, Peter Minuit, sent Pieter Barentsen to assume command of Fort Orange. Barentsen’s first task was to meet with the Mohawks. He got little satisfaction. The Mohawks simply pleaded that they had never before acted against the whites. Why had the Dutch meddled with them? Without that, they would never have shot them.

Barentsen’s second task was to remove the families. They would leave for the colony on Manhattan. The settlement at Fort Orange was over, at least for now. Only sixteen men would remain to garrison the fort. The episode was not so disastrous as to abandon the trade.

The setback was only temporary, of course. The Manhattan community, New Amsterdam, thrived in the coming years. As the Mohicans had predicted, the small people multiplied and filled up the land. Catalina Trico contributed her share. She bore eleven children. As an elderly widow, she guessed her progeny totaled 145. An estimate of her descendants four centuries later exceeded a million.

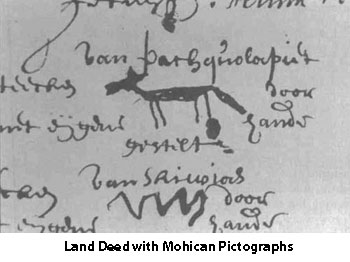

Within a couple of years, a clever Dutchman realized that perhaps he could turn the disaster into a boon. In 1628, Kiliaen van Rensselaer sent his agents up the Hudson. Many of the lands had gone vacant. It took two years to close the sale from the Mohicans. But to hear Van Rensselaer describe his purchase, it was worth the wait. His new Patroonship would comprise “the whole district with all the lands formerly inhabited by and belonging to the free, rich and well-known nation named the Mahikans. . .Since Daniel van Krieckebeeck … involved and engaged these same Mahikans in needless wars … [they] were so hard pressed … that they resolved in the years 1630 and 1631 to sell and transfer their said lands with all their rights, jurisdiction and authority … everything along the west side of the river, and inland indefinitely.”

Within a couple of years, a clever Dutchman realized that perhaps he could turn the disaster into a boon. In 1628, Kiliaen van Rensselaer sent his agents up the Hudson. Many of the lands had gone vacant. It took two years to close the sale from the Mohicans. But to hear Van Rensselaer describe his purchase, it was worth the wait. His new Patroonship would comprise “the whole district with all the lands formerly inhabited by and belonging to the free, rich and well-known nation named the Mahikans. . .Since Daniel van Krieckebeeck … involved and engaged these same Mahikans in needless wars … [they] were so hard pressed … that they resolved in the years 1630 and 1631 to sell and transfer their said lands with all their rights, jurisdiction and authority … everything along the west side of the river, and inland indefinitely.”

For the Mohicans, the defeat was the beginning of the end. The war lasted intermittently for two more years. Early in 1628, another battle broke out near Fort Orange. The Mohawks again defeated the Mohicans and vanquished them to the east, to the Fresh River, probably the river that would become the Connecticut. The Mohicans clung to some hope for a couple of years. They resisted selling their lands along the Hudson. But in 1630, they agreed to their first land transaction, though they likely did not understand they were permanently assigning the title to Kiliaen van Rensselaer. For many years, the Mohicans would reside at Stockbridge in Massachusetts, and they would become known as the Stockbridge Indians. About 1825, the prophecy of their forefathers was fulfilled. The strange race from the sunrise had grown as numerous as the leaves upon the trees and crowded them from their possessions. Chief John Quinney led them back to the west, to where the few remaining members of the tribe found a home at Green Bay in Wisconsin. The migration fulfilled only part of the prophecy, however. The Great Spirit had not averted a calamity.

For the Mohawks, their victory began a rise to domination. As the Mohicans said, the Dutch had laid the foundation for the future greatness of their Iroquois friends. The Mohawks began using Mohican lands with impunity, fishing, hunting, trading and warring. No longer would a Mohawk fear he would be hunted down as a beast of prey when he crossed the Mohican boundary. In the 1640s, the Reverend Johannes Megapolensis observed the Mohicans bringing annual tribute to the conquerors.

At about this time, the Mohawks obtained guns, first from the English, then from the Dutch. No matter the law, the traders could not resist the twenty beavers they could obtain for a musket or the ten guilders for a pound of powder. As the first Indians to use firearms, the Mohawks earned a new name from the River Indians for the gunlocks on their weapons– Sankhicani, the fire-striking people. Four hundred Mohawk warriors wielded guns to claim victories over their enemies along the St. Lawrence, who had so long held them at bay. With their new power, the Mohawks were feared by all the Indians around them, as far as the sea coast, and they compelled tribute from the weaker tribes. The Mohawk ascendancy would continue for over a century, until a new power emerged with the American Revolution.

No matter how tarnished and scratched, by wars, epidemics, land swindles or the flood of white immigrants, the Covenant Chain never actually broke. One end passed to the British in 1664 when the Dutch handed over their New Netherland colony. In 1700, the Five Nations of the Iroquois reminded the English governor of New York, the Earl of Bellomont. “We are of a peace,” the speaker Sadergenaktie said. “Our hearts are steady and constant, and we lay hold of the old Covenant Chain made with this government under the Crown of England, which we will keep firm and inviolable.”

At the next year’s conference, Lieutenant-Governor Nanfan, standing in for the dead Bellomont, reiterated the commitment from the English side. “There is a Covenant chain wherein all His Majesties Christian subjects on this main of America and the Brethren [the Five Nations] are included which I am now come to renew, according to the ancient custom. Let that be kept clean and bright on your parts as it is and shall be on ours.”

It was all a bit of a pretense, of course, a chain pitted with the chinks of war and covered in the rust of deceit. The Mohican sachem Soquans perhaps expressed it best at the 1701 conference in his message to the Lieutenant-Governor. After once again promising to keep the Covenant Chain inviolable, he reminded the governor how the links were kept shiny. “We have observed that neither Bears grease nor the fat of deer or elks are so proper to keep that chain bright. The only foreign remedy that we have found by experience in all that time to keep the chain bright is beavers grease.” And with that he handed over the item that bound the parties together, two pelts of beaver.

It was all a bit of a pretense, of course, a chain pitted with the chinks of war and covered in the rust of deceit. The Mohican sachem Soquans perhaps expressed it best at the 1701 conference in his message to the Lieutenant-Governor. After once again promising to keep the Covenant Chain inviolable, he reminded the governor how the links were kept shiny. “We have observed that neither Bears grease nor the fat of deer or elks are so proper to keep that chain bright. The only foreign remedy that we have found by experience in all that time to keep the chain bright is beavers grease.” And with that he handed over the item that bound the parties together, two pelts of beaver.

Go to: Part 1

Bill's Books

The Mevrouw Who Saved Manhattan

A Novel of New Amsterdam by Bill Greer

A "romp through the history of New Netherland that would surely have Petrus Stuyvesant complaining about the riot transpiring between its pages ... Readers are guaranteed a genuine adventure that will evoke the full range of human emotions. Once begun, they can expect to experience that rare difficulty in putting down a book before they have finished."

-- de Halve Maen, Journal of the Holland Society of New York

About the Book

_________________________

A DIRTY YEAR

Sex, Suffrage & Scandal in Gilded Age New York

A nonfiction narrative of 1872 New York, a city convulsing with social upheaval and sexual revolution and beset with all the excitement and challenges a moment of transformation brings.

From Chicago Review Press, 2020

More on the Book