In her radical ideas, Woodhull knew she pushed the limits. But how could the diseases of society be cured without speaking about them in plain language? In many ways, she invited the backlash that inevitably rose.

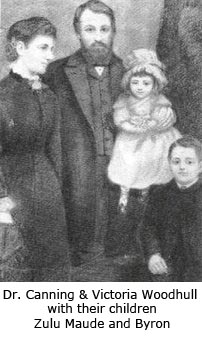

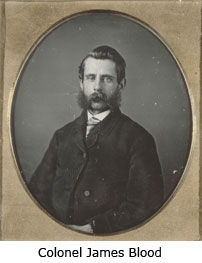

Early on, her critics attacked her personal life. At age fourteen, she had married Dr. Canning Woodhull. She soon bore two children, a lovely daughter Zulu Maude and a severely disabled son Byron. Dr. Canning proved a dissolute wreck, and the marriage broke apart. Woodhull remarried. Her husband Colonel James Blood played a large role in the sisters’ brokerage and publishing buisnesses and chaired Woodhull’s presidential campaign.

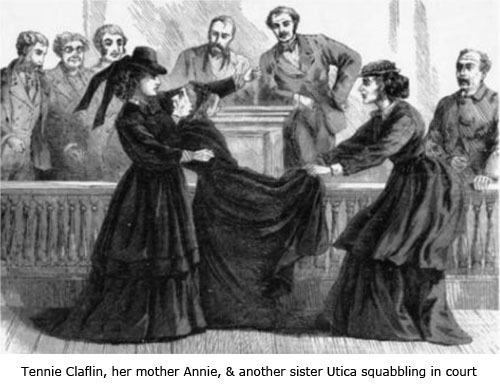

Woodhull’s extended family lived in the Murray Hill mansion she rented – her mother one bend away from the nuthouse, her father one step ahead of the sheriff, a host of unruly siblings, in-laws, nephews and nieces. In 1871, family squabbles spilled into the streets and then into the courts. Tales of violence, blackmail and insanity hit the press. The most damaging revelation was that Dr. Woodhull also lived there – two husbands under one roof and no one could tell a coherent story of when one marriage ended and the other began. Woodhull protested in a letter to the Times, saying her first husband, whose name she still bore, was ailing and incapable of caring for himself, Taking him in was not only her duty but “one of the most virtuous acts of my life." Who heard when the papers blared Free Love?

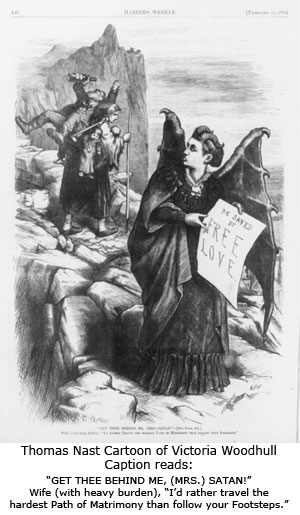

Yes, Free Love was another of the damning ideas Woodull espoused. In November 1971, she gave a speech in New York titled “And the Truth Shall Make You Free.” That night she portrayed her version of love as all about the sovereignty of the individual, about how society had no right to dictate how or with whom it was practiced. Her love was about freedom, about love infused with truth and purity. But her critics boiled all her controversial ideas down to this one and turned “free love” into an epithet equivalent to unbridled promiscuity.

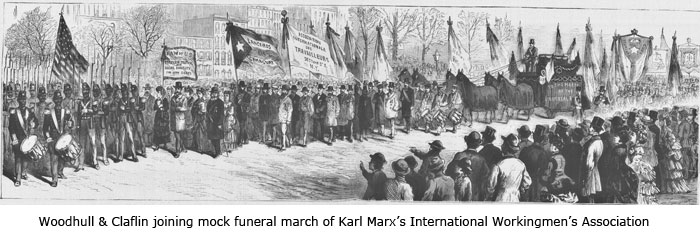

Things deteriorated further when Woodhull took a sharp left turn. Section 12, an American branch of Karl Marx’s International Workingmen’s Association, elected her honorary president. The Paris Commune had just collapsed, and the French Government had executed its leaders. With tens of thousands watching, Woodhull and Claflin joined a mock funeral march to honor them as martyrs. Early in 1872, Woodhull delivered another sold-out speech on “The Impending Revolution.” She excoriated leading captialists, calling out her patron Vanderbilt and others for oppressing the working class. Though she strode off the stage to thundering applause and a rain of bouquets, the press excoriated her.

The culmination of her demonizing came in the form of a cartoon. The city’s renowned Thomas Nast, whose drawings of Boss Tweed and his Tammany Ring had done as much as anything to bring about their downfall playing out at this time, drew an infamous cartoon labeling Woodhull “Mrs. Satan.”

Within weeks of her nomination for president, Woodhull’s campaign disintegrated. Ostracized, accused of blackmail, evicted from home after home, Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly shuttered, she was at last hauled into debtors’ court to declare she owned not even the clothes on her back. For weeks, as Woodhull and her family slept on the floor of the Broad Street office, she spiraled into despair.

Next: Part 4

Go To: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4

Bill's Books

A Novel of New Amsterdam

The Mevrouw Who Saved Manhattan

"[A] romp through the history of New Netherland that would surely have Petrus Stuyvesant complaining about the riot transpiring between its pages."

- de Halve Maen, Journal of the Holland Society of New York