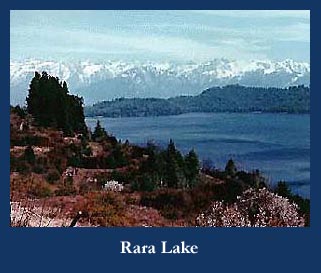

Blue Jewel

Rara Lake, Nepal, 1988

[Full story also available as a PDF download]

“BRING A BOTTLE OF IMPORTED WHISKEY,” Shiba said. “I’ll get one, too.” Our trekking agent had been trying for months to book us on a flight to Jumla, a remote village in western Nepal. We wanted to visit the national park at Rara Lake, and we either caught a plane or walked in for 10 days. He had decided it would take more than buying tickets to get us in the air and thought he had hit on the proper inducement.

We had already abandoned flying from Khatmandu. “We could charter a plane,” Shiba proposed. “That will cost a couple of thousand dollars.” “Not likely,” I said. “Any other suggestions?”

We had already abandoned flying from Khatmandu. “We could charter a plane,” Shiba proposed. “That will cost a couple of thousand dollars.” “Not likely,” I said. “Any other suggestions?”

“I can take you to Nepalganj. It’s a town on the Indian border, where I take my wife when she wants to cross over for shopping. We might be able to get a flight from there.”

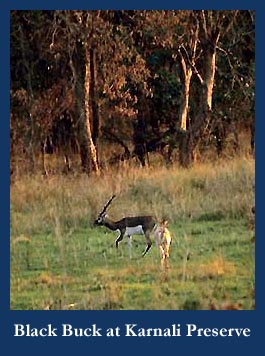

It seemed worth a try. It would also give us a chance to visit Karnali Preserve to view game. We scurried around Khatmandu, trying to find whiskey at an affordable price. We finally gave up and bought a fifth of Johnny Walker Red from our hotel for $80. The price of our plane ride had doubled.

A guide and driver from Karnali picked us up when we arrived in Nepalganj. We piled into a beatup land rover and headed for the Royal Nepal Air office. “You stay here,” the guide instructed my wife Diane. The rest of us trooped in to meet the Regional Manager. He was a jovial rotund man with beady eyes blurred behind the coke bottle lenses of his spectacles. “Namaste,” he welcomed us with the by-now familiar greeting. “Where are you from? Do you like Nepal?” We settled in for the pleasantries that precede any business in Asia.

Eventually the talk turned to our quest. “The flights to Jumla are full. Many people want to go there and we do not have enough planes.” I smiled, confused as to how this game was played. The Karnali driver brought out our blank tickets. “If I give seats to foreigners,” the manager continued as he handed the tickets to his assistant, “people will think I am selling places on the black market.” Shiba picked up a signal from someone and shuffled through his bag. He pulled out a bottle wrapped in newspaper and motioned to me. I laid my bundle beside his.

Eventually the talk turned to our quest. “The flights to Jumla are full. Many people want to go there and we do not have enough planes.” I smiled, confused as to how this game was played. The Karnali driver brought out our blank tickets. “If I give seats to foreigners,” the manager continued as he handed the tickets to his assistant, “people will think I am selling places on the black market.” Shiba picked up a signal from someone and shuffled through his bag. He pulled out a bottle wrapped in newspaper and motioned to me. I laid my bundle beside his.

As his assistant validated our tickets, the manager slid the packages into his desk. “You are lucky. Some Americans came last week and I could find no seats.. They got very mad. I told them they would have to hire a charter.” I had learned enough about Asia to know that anger was a fatal mistake. That group might as well start walking.

We concluded our visit with a friendly farewell. A couple of days later, we jostled our way onto a plane, wondering what we would find when we touched down a 10 day hike into the Himalaya. Jumla did not sound like a place where we could check into the local bed and breakfast. “Don’t worry,” Shiba assured us. “Dendi started walking in with your trekking crew almost two weeks ago. He will meet you.”

As the crowd began to disperse from the field where we landed, we looked around with trepidation. Finally a thin young man approached. “Namaste. I am Dendi.” We smiled with relief, and excitement at the adventure ahead.

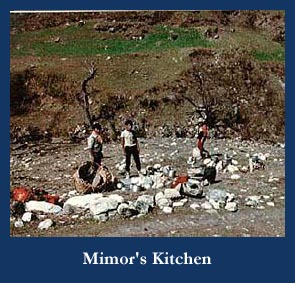

THE NEXT MORNING WE SET OUT. Our cook Mimor and his two assistants packed up the camp. The kitchen boys Bimba and Tilok shouldered the lighter baskets. The guide Dendi assigned three porters to the heavier loads. He carried a small daypack himself. The camp hierarchy was becoming clear.

“We’ll reach Rara Lake in four days,” Dendi told us. “We’ll stop for lunch today when we find water.” We started up the avenues of Jumla, a bit out of breath from the eight thousand foot altitude. Two hours later we were glad to sit down while Mimor cooked, but didn’t feel too fatigued. The slope had been gradual, and we had kept a good pace.

By mid-afternoon our illusions were shattered. A sheer ridge loomed before us, with a trail snaking straight up. Mimor bounded ahead, passing sheperds effortlessly chasing their goats in the alpine meadows. I struggled to lift one foot. About halfway up, I reached for my altimeter. “Don’t look,” Diane warned. “Almost 11,000 feet,” I read. “My lungs are bursting. I don’t want to know!” she screamed back. At 12,000 feet, we topped the crest, only to stare down at the north side covered with snow, ice, and mud. I tried the snow first, off to the side. A couple of steps later, I plunged thigh deep, unable to extricate myself, much less move forward. Diane stuck to the ice and mud on the main path. She managed to stay erect for 20 paces, then slid several yards into a snowbank.

Slowly we edged our way down a valley, catching Mimor as dusk closed in. The mountains rose steeply on both sides of the stream, with snow blanketing everything. A stone building housing a smoky teashop occupied the only level ground.

“Do you think they expect us to stay in there? Diane asked.

I frowned, seeing no alternative. “We can’t pitch our tent on this snow and we’ll slide down the bank anyway.” We peered again into the hazy interior.

Mimor must have seen us blanch. He barked orders and pointed at the mud roof. The boys scrambled up and unfolded the tent. Sure enough, he had spied the only flat dry spot available. We learned quickly never to doubt his eagle eyes when he was looking after our comfort.

“I wanted to stay in Australia,” I taunted that evening. “Didn’t the guide books say to take a short easy trek the first time, see if you like it?”

“You talked me into this,” Diane said. “A twelve thousand foot pass on the first day. How many more?”

Some hot tea calmed me. “The first day is always the hardest,” I rationalized.

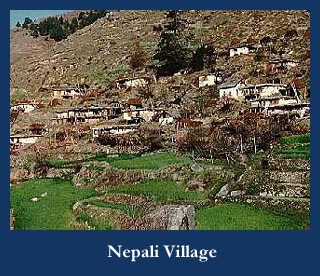

We dragged ourselves up the next morning and kept walking. Three days later we had forgotten those initial tribulations. We traveled down one river valley and up another. We passed countless villages, with schoolchildren chasing us as we brought some excitement to their recess. We hiked across terraces dotted with blooming peach trees and through dense evergreen forests.

We dragged ourselves up the next morning and kept walking. Three days later we had forgotten those initial tribulations. We traveled down one river valley and up another. We passed countless villages, with schoolchildren chasing us as we brought some excitement to their recess. We hiked across terraces dotted with blooming peach trees and through dense evergreen forests.

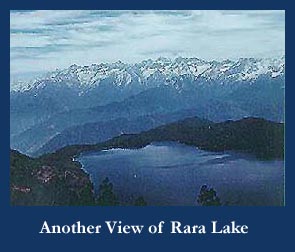

Atop another 11,000 foot pass, we glimpsed our destination, a shimmering blue jewel set in a ring of snowy peaks. The next day we camped on the shore of Rara :Lake.

“HOT TEA,” the kitchen boy Bimba roused us each morning. The steaming brew sweet with milk and sugar would be followed with a hot breakfast: oatmeal or rice porridge, a fried or scrambled egg, warm juice.

Mimor had learned to cook in the Indian army. He ran his kitchen with military discipline, ordering Bimba and the second helper Tilok to scrub pots, pack supplies, or carry out a myriad of other chores. Late in the day, he would scan the horizon, looking for a level spot with a supply of flat rocks. “Up there,” he would gesture excitedly, and we would climb the fallow rice terraces to the one he spied for tonight’s kitchen. He would send one of the boys for firewood, while he configured the stones into an oven and stove. Soon the pots and food packages would be strewn haphazardly across the ground, a breakdown of the military order. He would begin rattling his cast iron skillet over the open flame, popping the corn that would serve as the hor’doerves for the evening’s dinner. Soup would come next, spicy tomato or chicken, then a main course of french fries or curried potatoes, rice with lentils, tuna, apple pancakes, poori. The fare was frequently enough to feed a brigade. Dendi had first call on leftovers and passed whatever remained down a rigid pecking order.

“Mimor promises a special surprise tonight,” Dendi informed us the day after we reached Rara Lake. The cook had disappeared after breakfast, off to search for this treat. The rest of us were relaxing to celebrate our arrival, Dendi studying Japanese for an anticipated wave of East Asian trekkers, our porters bathing for the first time in more months than they could remember.

When we wandered back to camp after an afternoon exploring the abandoned villages around the lake, the controversy over the evening meal was flaring up. “Take this and do it.” Mimor held out his kukri, the traditional knife of the Gurkha soldiers. Tilok backed away. Two chickens flopped on the ground, their feet bound. Mimor had purchased them at a village to the south, apparently the only fowl within a few hours walk. We hoped our eggbox was already supplied.

When we wandered back to camp after an afternoon exploring the abandoned villages around the lake, the controversy over the evening meal was flaring up. “Take this and do it.” Mimor held out his kukri, the traditional knife of the Gurkha soldiers. Tilok backed away. Two chickens flopped on the ground, their feet bound. Mimor had purchased them at a village to the south, apparently the only fowl within a few hours walk. We hoped our eggbox was already supplied.

The Nepalis looked at one another uneasily. Dendi motioned to one of the porters. “Not me,” he stammered and hurried away to his own fire. He may have been the low man on the totem pole, but his responsibilities were carrying equipment, not preparing dinner.

We watched with amusement. Nepalis tormented their animals constantly. Yesterday, we had passed a young herder beating his cow furiously over the head as it straddled a fence, unable to escape. Our trekking crew loved to aim rocks at anything that moved, lizards sunning on boulders, monkeys in the rice fields. But with their Buddhist background, the taking of a life was a serious offense. No one wanted to earn the demerits of beheading the hens, especially at Rara Lake, renowned as a Buddhist shrine.

Mimor turned on Bimba next. The cook himself couldn’t back down. Even if he overcame his religious zeal, he had to maintain discipline. Bimba was more timid than Tilok, much less likely to put up a strong resistance. He realized he was defeated. He picked up the fowl and trudged up the slope. At least if he got away from the lake’s sacred waters, he could lower the marks against him.

Following the usual popcorn and soup, the chicken was served with a flourish. Mimor selected the well-rounded thighs, the meatiest part of what were really scrawny birds. We bit into the dark flesh and began to chew - and chew and chew. The pride which had gone into this delicacy was evident, but it had come out like a rubber ball. Nepali chickens forage for their food. The diet and scratching in the dirt had toughened these birds. “Nepali racing chickens,” Diane said as she swallowed the first mouthful. I laughed half-heartedly, eying the remaining pieces that we needed to stomach one way or another.

But Mimor had not yet completed the surprise. His desert had a golden crust, apple pie needing only a little sugar sprinkled on top to sweeten the sour fruit. Even without cinnamon, sharp cheddar, or ice cream, the meal was redeemed.

THE ELDERLY MAN with rolled beard and turbaned head laid the cloth on the tarp that served as our rest area and dining table. He was one of many travelers that passed our camp at Rara Lake along the trade route from Gumghari out to the roadhead at Surkhet. Most stopped, either to trade food and staples with the cook Mimor, exchange news, or simply gawk at the Westerners while they rested their loads. This gentleman had interesting merchandise to offer.

He unfolded the bundle and displayed the coins it contained. He pulled out a pair of ancient round spectables and picked up a coin for examination. “This one is silver, from King Tribuhan’s reign.” Our guide Dendi inspected it, flipping it in the air to hear its ring. “Sounds real. It must be about 100 years old.” “Yes,” agreed the trader. “Here, this one is older, 250 years.” Dendi passed the first around.

“People find these in the mountains once in awhile. I know how valuable they are so I collect them.” Dendi appeared intrigued.

“500 rupees for that one,” the man offered for the second coin. That amount translated to $25, about a week of a guide’s pay.

Dendi whispered it would fetch much more in Kathmandu. “Expensive,” he countered. After several rounds of negotiation, they settled on a price of 200 rupees.

Now that the interest had been established, the man held up another coin. The gold shined yellow in the sun. “This is very, very precious, from the Malla kingdom.” That medieval dynasty had ruled Nepal during the 13th century. We drew closer to examine the curlicues minted into the metal. Dendi flipped the coin. “No,” Mimor argued, “the ring will not tell whether gold is real. Give me the coin.” He rubbed it in his hair and inspected the lustre. “It’s a good alloy,” he determined. I wasn’t too confident in his powers of assay. “15,000 rupees,” offered the seller. Under $1000 sounded reasonable for a 700-year old coin of pure gold. Did we want to gamble on its authenticity?

Dendi was wrenching. He could resell it for several months pay if he could bargain down the price. But he had nowhere near enough money to finance the transaction. He looked at me. I shook my head. Unless the trader accepted travelers checks, I could not come up with the cash either, and the risks of forgery, violation of the antiquities laws and who knew what else were too great for my tastes.

Dendi sulked but in the end traded for the other silver coin. We satisfied ourselves with photographs of the gleaming metal.

WE STAYED AT RARA LAKE 3 DAYS. It had once been a thriving community with villages around the shore. The residents were relocated a decade before to create the national park. The lake was a clear deep blue, resting in a hanging valley. At the north end, the land fell abruptly down to the Mugu River, with 20,000 foot towers beyond. Similar peaks closed in the other sides, perfectly reflected in the water’s morning calm. The spectacular setting warranted preservation, but it was easy to sympathize with the displaced locals who were moved to the hot grasslands bordering India. The only establishments remaining were a post office and park headquarters. The ranger’s log informed us we were the twelfth and thirteenth foreign guests of the year.

The final evening, we steeled ourselves for the long haul out. No airplanes this way. Diane perused the map. “A quick shot down the Khotyar River, over a ridge to the Singa River, follow it to the Tila River, then over a ridge to Dailekh. We’ll be halfway there.”

I groaned. Each of those ridges represented a pass which might dwarf the one we climbed the first day out.

The countryside appeared prosperous. The villages contained slate-roofed houses, white-washed and adorned with orange ribbons and potted cacti. The valleys were heavily terraced and cultivated with rice and lentils. The river fueled an elaborate mill system, with water channeled through wooden chutes into small buildings housing the wheels and grindstones.

The countryside appeared prosperous. The villages contained slate-roofed houses, white-washed and adorned with orange ribbons and potted cacti. The valleys were heavily terraced and cultivated with rice and lentils. The river fueled an elaborate mill system, with water channeled through wooden chutes into small buildings housing the wheels and grindstones.

But prosperous did not mean worldly. “I count twenty, five adults and a bunch of kids,” I reported on the crowd peeking in our tent. We had gotten used to staring, ever since the first goatherd had squatted down and lit his pipe when Diane motioned that she intended to bathe. Here the whole village had turned out. “What shall we take for entertainment?”

We selected the binoculars and passed them slowly down the line, teaching what to look through and how to focus, though frequently unsucessfully. These proved to be of limited interest. We proceeded to the mirror. The children had seen their reflections before but here was something new. Each child cackled as he gaped at the larger-than-life size image that came back from the magnifying mirror in Diane’s compact. The adults were no less delighted.

“How about a game?” I suggested.

“Sure, cut some rope and we’ll see if we can remember the figure eight string game.”

We couldn’t get past the third stage, but our repeated failures amused the group. We gave the rope to some girls. They had no more success. By now, we were tiring of the attention. Mimor’s pressure cooker suddenly emitted a sharp hiss as it let off steam, distracting the crowd. We beat a hasty retreat behind our tent flap.

These crowds were now the norm as we trekked through an area that had seen few westerners. At lunch, we brought out pictures from home for a group of teenagers. “Malcolm and Shorty,” I pointed at our cats. The boys pulled the pictures close to their eyes, not comprehending the image. Cats live in Nepal, so I was puzzled at their astonishment. I learned later that travelers for a century have observed South Asians who could not visualize a three dimensional object from a photograph.

The terrain proved as trying as the map had implied. “Dendi looks confused,” Diane said when we stopped the first night from the lake.

“He’s lost. We came too far down the valley.” I had been reading trail descriptions.

Our guide sought directions from a firewood supplier, who appeared to know little more. The turbaned gentleman from our coin exchange happened by. He waved into the mountains. The next day Dendi sheepishly led us up that path. Seven hours later we had climbed a mile upward and hit snow. Fortunately the top was in sight.

That pass was the first of several over 11,000 feet. We soon realized we had it easy. The trek to Surkhet was on a highway, with vehicles of goats, a few horses, and men. The goats were outfitted with woolen sidebags to carry salt between Tibet and India. The horses carried heavier loads, but had to detour around a long vertical stretch of trail. Men were the principal beasts of burden. They carried enormous loads, secured on their backs with a tump line around the forehead, up slopes which we struggled to scramble down. Cement, corrugated roofing tin, loops of irrigation hose. They eyed the ligher loads of our porters with envy.

As we traveled south, signs of civilization increased. Tables and chairs appeared in the teashops. Travelers carried radios and wore T-shirts from California. Dailekh was a metropolis, with well-stocked groceries, pharmacies, and clothiers. Twelve days from Rara Lake, we hit a gravel roadbed which would take us down to Surkhet. Washouts would have sent any vehicles tumbling down the mountainside so we still had a day’s descent under our own power. By mid-afternoon, we strolled along main street Surkhet, dodging trucks and eying chocolate bars. We had trekked 150 miles in 3 weeks, encountering one other westerner, a Swiss medical student who camped with us at the lake.

“One last peaceful night,” I remarked as we zipped up the tent. Tomorrow we would catch the bus back to Nepalganj. Suddenly, the sounds of a loudspeaker drifted across the field, electric lights blinked on in the surrounding buildings. Civilization had returned.

Originally published 1996.

Bill's Books

A Novel of New Amsterdam

The Mevrouw Who Saved Manhattan

"[A] romp through the history of New Netherland that would surely have Petrus Stuyvesant complaining about the riot transpiring between its pages."

- de Halve Maen, Journal of the Holland Society of New York