Click on any picture to pop up an enlargement

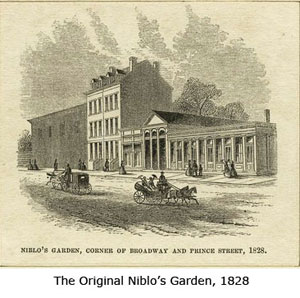

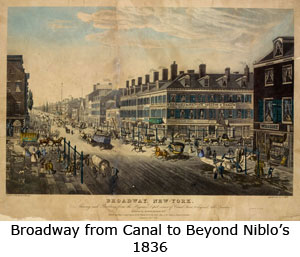

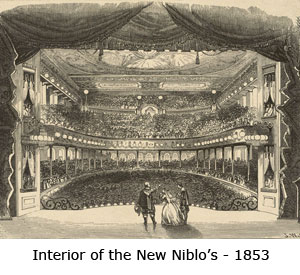

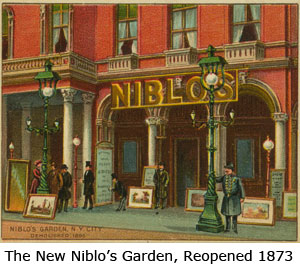

Niblo’s Garden was a venerable name in the theater business. Its first shows dated back to the presidency of Andrew Jackson. The finest Shakespeareans and grandest divas graced its stage. Its audiences witnessed New York debuts of Italian operas, the dancing of the polka, and the military antics of the French Zoaves. The original theater at the corner of Broadway and Prince Street burned in 1846. Newly rebuilt on the same spot, Niblo’s reopened in 1849.

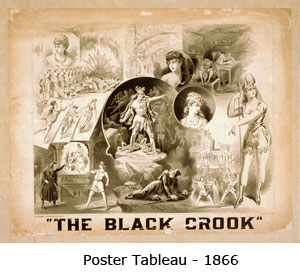

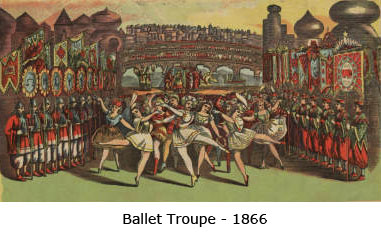

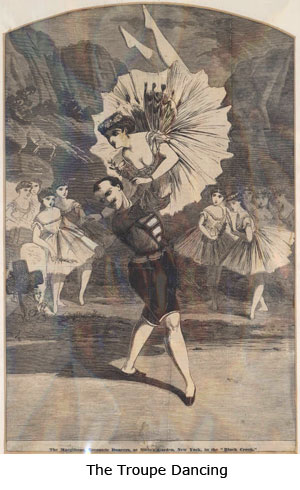

The theater’s greatest triumph opened on a September evening in 1866. The ballet corps of The Black Crook pranced out before an overflow crowd. For six hours, the dancers exhibited a charm, beauty, and grace never before seen in America, or so judged the critic of the New York Evening Post. The New York Times was less kind, describing dancers wearing no clothes to speak of performing “such unembarrassed disporting of human organism [as] has never been indulged in before.” Both papers concluded the show would be a tremendous success. When the initial run ended four hundred seventy-four performances later, no one could argue.

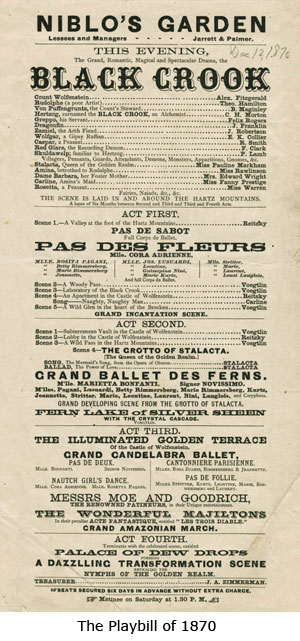

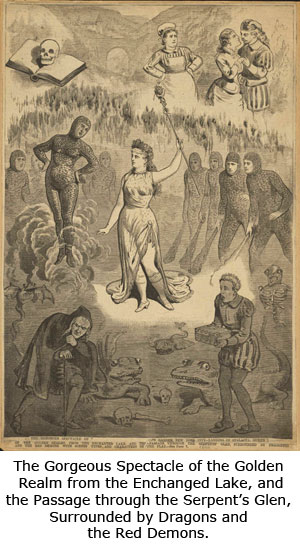

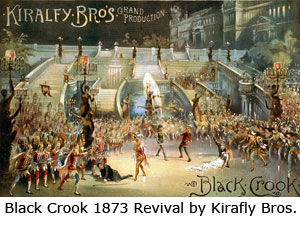

The 1866 production starred Maria Bonfanti as Stalacata, Fairy Queen of the Golden Realm in Germany, 1600. Stalacata saves the simple villager Rodolphe from the designs of Count Wolfenstein, who lusts after his fiancé Anima. The Count has enlisted Hertzog – the “Black Crook,” to capture Rodolphe. Hertzog has a deal to sell one soul each year to the devil in exchange for immortality. Rodolph is this year’s victim. Queen Stalacata rescues Rodolphe from Hertzog’s clutches as her army defeats the Count’s forces. Demons drag Hertzog to hell. Rodolphe and Amina live happily ever after.

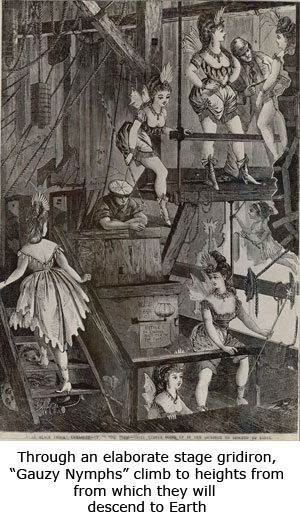

So much for the plot, which had nothing to do with the play’s acclaim. Audiences flocked to it for the burlesque – song, dance, buffoonery and sparsely-covered flesh. The playbill offered such dazzling numbers as “Naughty, Naughty Man,” a “Grand Amazonian March,” and “A Dazzling Transformation Scene Revealing the Nymphs of the Golden Realm.”

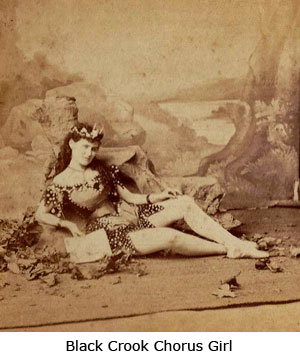

Photographs of the leading ladies and the ballet corps sold briskly. During a revival in the early 1870s, the vice hunter Anthony Comstock, just beginning his forty-year battle against obscenity, indicted one smut dealer reportedly for selling photos of dancers in the Black Crook. Their legs outlined in tights beneath short skirts were too risqué for the judge as well. He sentenced the dealer to one year’s imprisonment at hard labor and a $500 fine.

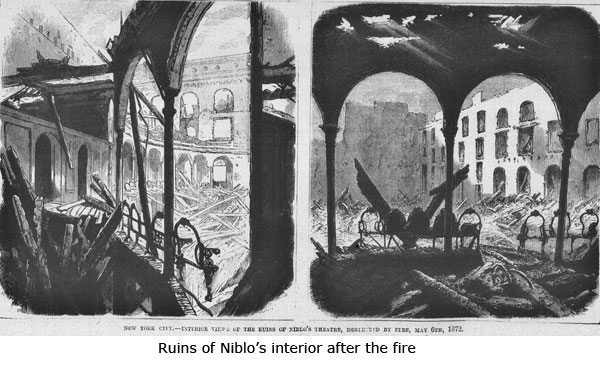

Niblo’s 1872 revival of The Black Crook was a sort of last hurrah for the theatre. Three months after the close, Niblo’s burned to the ground a second time. The New York Herald delivered a eulogy. With the Black Crook, Niblo’s had inaugurated a new era of gaudy spectaculars, the paper said. While lamented by respectable society, these proved enormously popular among the public, particularly for those enjoying “an exhibition of leg development.” In this “corruption of the popular dramatic taste Niblo’s has been the principal sinner, and the baneful and demoralizing influence it exerted was felt from one end of the Union to the other.”

The eulogy was premature. Niblo’s again rose from the ashes. In a new building, its fourth revival of “The Black Crook” opened on August 18th, 1873. The Herald described “the event as far from literary as possible, and with very little affinity to anything dramatic.” But the critic admitted that “if the size of the audience is any criterion from which to judge of the success of the piece it will have another long run.”

THE BLACK CROOK TODAY:

Brooklyn's Green-wood Cemetery holds an annual tribute to its permanent resident William Niblo with a weekend of The Black Crook. Green-wood says: "Begin the evening with a picnic (bring your own) around beautiful Crescent Water before being dazzled by nineteenth-century showmanship: fire eaters, musicians, contortionists, performers on floats, and much more—all under the starry summer skies." More at Green-Wood Cemetery, A Night at Niblos.

Bill's Books

A Novel of New Amsterdam

The Mevrouw Who Saved Manhattan

"[A] romp through the history of New Netherland that would surely have Petrus Stuyvesant complaining about the riot transpiring between its pages."

- de Halve Maen, Journal of the Holland Society of New York