Broken Chain

How the White and Indian Worlds Remembered Henry Hudson and the Dutch

Part 2 of 3

Go to: Part 1 - Part 2 - Part 3

[Full story, with Endnotes & Bibliography, also available as a PDF download]

IN TIMES OF OLD, THERE WERE NO CHRISTIANS ON THE RIVER, the Mohican sachem Soquans told the New York governor and his council in 1700. The first Christians that came settled upon Rensselaer’s Island, he said. We loved them as soon as we saw them, and received them as Brethren, and we made a strict alliance and a Covenant Chain which has been kept always inviolable ever since. A year later, Soquans returned before the Council. In ninety years, he reiterated, there has never been a crack in the Chain. Though there had been breaches and great differences, that Chain wherein the Mohawks and the Mohicans are linked has been kept inviolable and we pray that our Fathers will keep the same so forever.

The Mohicans’ memory was vivid, extending back to the first white men and beyond. It was recorded in belts of wampum that marked the important events of the tribe, a treaty, a call to war, the death of a sachem. The wampum belts strung together seashells, the colors and patterns signifying the message. White wampum denoted good tidings as in peace and friendship, and if white shells were unavailable, chalk or clay would be daubed on colored ones to make them white. Black was more ominous, as in the black belt painted with a red hatchet that invited an ally to war. A sharp orator would wield a belt as he spoke, turning it just so to signal how far his speech had progressed and pointing to the places on the belt which corresponded to the elements of his message.

The Mohicans’ memory was vivid, extending back to the first white men and beyond. It was recorded in belts of wampum that marked the important events of the tribe, a treaty, a call to war, the death of a sachem. The wampum belts strung together seashells, the colors and patterns signifying the message. White wampum denoted good tidings as in peace and friendship, and if white shells were unavailable, chalk or clay would be daubed on colored ones to make them white. Black was more ominous, as in the black belt painted with a red hatchet that invited an ally to war. A sharp orator would wield a belt as he spoke, turning it just so to signal how far his speech had progressed and pointing to the places on the belt which corresponded to the elements of his message.

To invest the memories throughout the tribe, the people gathered at certain seasons. The historian, the keeper of the wampum, would remove a belt from the bag where it was stored and say aloud its meaning. The belt would be passed among the people, and each repeated its message, so that at least once a year, every person, male and female, recited the meaning of the belts. Periodically Grand Councils would be held, where over two moons the memories were recited to compare stories, correct differences and pass the knowledge down the generations.

These memories passed to the white men through conferences with the colonial authorities, Moravian missionaries who lived among the Indians, even in a speech at an 1854 celebration of the white man’s independence. The chief John Quinney remarked on that irony as he sharply chastised his listeners over their treatment of the Mohicans. At the last Grand Council the Mohicans convened, circa 1750, two of their young men, students of the Moravians, committed their tribe’s history to paper, and though it was feared lost, a portion written by Hendrick Aupaumut was rediscovered.

The story that led the Mohicans to the Covenant Chain began thousands of years before the white man’s coming. Their ancestors came from the Northwest, crossed over the salt-waters, and after a long and weary pilgrimage, built their fires upon the Atlantic Coast. Here the people dispersed into many tribes. The Delawares would remain the Grandfather of the River Indians. Others drifted south to the Potomac or north to the Penobscot. One group settled where the waters flowed and ebbed, and they took the name Muh-he-con-new – “like our waters, never still.” The waters were the Hudson, and the newly-named Mohicans occupied its valley from the tidewater to Lake Champlain.

The land was rich in game, fertile in soil and free of disease. The tribe seldom felt want, easily finding the food and raiment which was their only aim. Every year, delegates would go to a Council of all the related River Indians and deliberate on the general welfare and invoke the blessing of the Great and Good Spirit. The tribes remained so united that whoever attacked the one, it was the same as attacking the whole, and they would make common cause against the enemy.

Though the Mohicans distinguished themselves in their peaceableness and taught their children to be kind and generous, their men were the best warriors in the field, truly formidable to any nation and acknowledged so by the unrelated peoples living to the west. On the eve of the white man’s arrival, they numbered 25,000 and could lead four thousand warriors into battle. With their strength, they lived in peace. Friends could cross their borders, enemies feared to. A Mohawk appearing in their country knew he would be hunted down as a beast of prey.

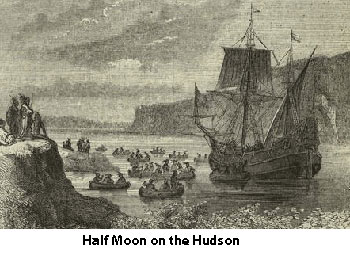

One day a Mohican walked out of the castle the tribe had built on the river. He saw something on the water. At first he thought it was a great fish, and he ran to the castle to call others to look. Two of the men went to examine it closely. They discovered a vessel with men in it. They immediately joined hands with the people in the vessel and became friends. Though the Mohicans did not record the names, the ship was the Half Moon and her commander was Henry Hudson.

One day a Mohican walked out of the castle the tribe had built on the river. He saw something on the water. At first he thought it was a great fish, and he ran to the castle to call others to look. Two of the men went to examine it closely. They discovered a vessel with men in it. They immediately joined hands with the people in the vessel and became friends. Though the Mohicans did not record the names, the ship was the Half Moon and her commander was Henry Hudson.

The Mohicans were astonished at the pale faces of the visitors and thought the white men must be ill. When the strangers asked for rest and kindness, the Mohicans took them in, naked as they were, and clothed them. The white men said they would not stay, but they promised to return in a year’s time.

In remote times, the wise men of the Mohicans had foretold the coming of a strange race from the sunrise, as numerous as the leaves upon the trees. The strangers would eventually crowd them from their possessions, the ancestors had predicted. Still, as the white men sailed away, the Mohicans suffered little anxiety, for the prophecy also said that this land was not their original home and that one day they would return to the west from whence they had come. The Great Spirit who had made the red men from red clay would unite their strength to avert a calamity.

So when the white men returned, the Mohicans welcomed them ashore and said to them, we will give you a place to make a town, from here up to such a stream and from the river back up to the Hill. You are a small people, they told the families who had come to settle, but in time you will multiply and fill up the land we have given you.

After the white men were ashore for some time, other Indians came, ones who had not seen the strangers before. They looked fiercely at the newcomers. The Mohicans, seeing the threat and the whites so few in number, took and sheltered their visitors under their arms, lest they be destroyed.

Another Mohican sachem, Solomon Wahaunwanwaumeet, reminded the whites of this kindness a century and a half later. “You remember when you first came over the great waters,” he told a Provincial Congress in 1774, “I was great and you was very little, very small. I then took you in for a friend, and kept you under my arms, so that no one might injure you; since that time we have been true friends.”

And how did the whites repay the kindness? They did what no other nation could have done, that’s what the Mohicans concluded. The Dutch turned the Mohicans into women. And in doing so, they laid the foundation for the greatness of the Iroquois. The Iroquois, the confederacy of the Five Nations in which the Mohawks played the role of eldest brother. The Iroquois, who the Dutch called friend. The Iroquois, who the Mohicans called enemy, an enemy they were on the verge of extirpating before the white men interfered.

The conspiracy began when the Iroquois found themselves between two fires, squeezed by war with the French and their Algonquin allies to the north and the Mohicans and their grandfather the Delaware to the east and south. Realizing they could not prevail, the Iroquois turned to intrigue. They must persuade their enemies to lay down their arms, they decided, convince them that the wars would exterminate them all if they could not be ended.

What was needed was a people who would assume the role of mediator among the warring neighbors. A people who would assume the role of women, who would become women. For it was always the women who ended wars. A man would never express a desire for peace. No matter how tired, he would fear being called a coward. A warrior must show courage to the end, never hold the peace belt in one hand and the tomahawk in the other.

But the tender and compassionate sex would come forward and lament with great feeling the losses suffered. The women would describe the sorrows of widowed wives and bereaved mothers. They would cry how cruel it was to see their sons slaughtered on the field of battle or tortured as prisoners. When the warriors began to pity the suffering of their wives and helpless infants, the women would argue that both sides had proved their courage, that the contending nations were alike high-minded and brave. Now they must embrace as friends those whom they respected as enemies.

This the Iroquois told the Mohicans and the other River Indians. Some magnanimous nation must assume the situation of the woman. A weak or contemptible tribe could not play the role for no one would listen. No, only the River Indians commanded the respect and influence. As men they were dreaded; as women they would be honored and could stop the quarrels and the bloodletting. If only they would lay down their arms, they would bring peace and harmony to the nations.

The Mohicans would not be so easily fooled. But the Mohawks told the Dutchmen who had penetrated their country that they were warring against the Mohicans. And the Mohawks said they would not suffer the Dutch to trade with their enemies, that the Iroquois were the most powerful of all the Indian nations and if the whites were friends to their enemies, the Five Nations would turn their full fury on them. But if instead the Dutchmen helped them bring peace with the Mohicans, then the Mohawks would support and protect the white men in all their undertakings. The white traders were afraid, for they had seen great bodies of warriors pass and repass and they could not avoid being disrupted and molested.

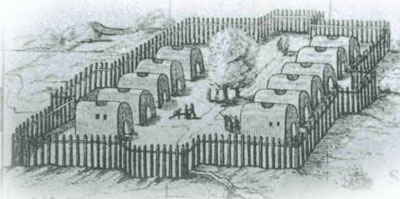

So the Dutch called a grand council, and the Mohicans and the Mohawks gathered on the banks of a stream near where the Dutch had built their fort, a stream to be known as Nordman’s Kill. With many speeches and supplications, the white men got the hatchet out of the hands of the River Indians. They buried the weapon and said that they would build a church over the spot so that the weapon could never be stolen except by lifting up the whole church. If any nation dared to steal it, the Dutchmen promised to take revenge on them.

Then a great ceremony was held to invest the River Indians in the role they had accepted. “We dress you in a woman’s long habit, reaching down to your feet, and adorn you with earrings,” the Mohawks told the River Indians, and delivered a belt of wampum. “We hang a calabash filled with oil and medicine upon your arm,” they continued. “With the oil you shall cleanse the ears of the other nations, that they may attend to good and not to bad words, and with the medicine you shall heal those who are walking in foolish ways, that they may return to their senses and incline their hearts to peace.” The Mohawks delivered another belt of wampum, and then a third as they concluded. “We deliver into your hands a plant of Indian corn and a hoe.”

And with the River Indians installed in the situation of the woman, a great belt of wampum and chain of friendship was laid across their shoulders as the mediators, and one end was held by all the other Indian nations and the other by the Dutch.

Go to: Part 3

Bill's Books

The Mevrouw Who Saved Manhattan

A Novel of New Amsterdam by Bill Greer

A "romp through the history of New Netherland that would surely have Petrus Stuyvesant complaining about the riot transpiring between its pages ... Readers are guaranteed a genuine adventure that will evoke the full range of human emotions. Once begun, they can expect to experience that rare difficulty in putting down a book before they have finished."

-- de Halve Maen, Journal of the Holland Society of New York

About the Book

_________________________

A DIRTY YEAR

Sex, Suffrage & Scandal in Gilded Age New York

A nonfiction narrative of 1872 New York, a city convulsing with social upheaval and sexual revolution and beset with all the excitement and challenges a moment of transformation brings.

From Chicago Review Press, 2020

More on the Book