Sex and the City: The Early Years

A Bawdy Look at Dutch New York

Part 3 of 3

Go to: Part 1 - Part 2 - Part 3

[Full story also available as a PDF download]

The Roots of Rebellion

WHERE DID ALL THIS debauchery lead? The Directors appointed by the West India Company thought the answer was down the path to perdition. In a sense, they were right for the bawdy behavior was one sign of a rebellious streak that would lead to conflict throughout the era of New Amsterdam. The roots ran far deeper than bad behavior, however. The conflict really turned on economics – who would reap the benefits of the fur trade, the West India Company or the people – and politics – who would govern the place, the appointees of the Company or the people themselves.

Trouble started at the very beginning. Willem Verhulst came as the first Director in 1625 and established the settlement at the mouth of the Hudson, first on Governor’s Island, then on Manhattan. He ruled with a hard and arbitrary hand, or so the people thought. No matter they were sworn to obey, before a year was out they set up their own court and put Verhulst on trial over his intemperate rule. While we don’t know precisely what his crimes were, he was deposed and banished from the colony. He didn’t do himself any favors hearing his sentence. If he were not serving the honorable gentlemen of the West India Company, he threatened, he knew other masters who would want his services and he knew how to avenge himself. He perhaps had the English or French in mind.

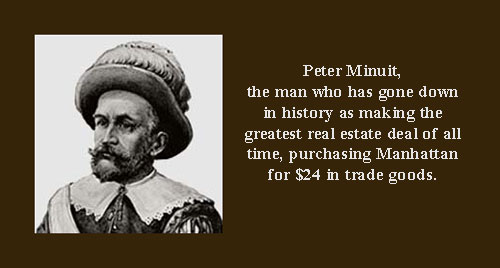

The presumed ringleader of the rebellion was elected to replace Verhulst – the man who had come as his lieutenant and who has gone down in history as purchasing Manhattan from the Indians for 24 dollars, Peter Minuit. His takeover wasn’t the last sign of a rebellious streak in Minuit. After the Company recalled him a few years later, he carried out the act Verhulst only threatened. He went to work for the Swedes,

The presumed ringleader of the rebellion was elected to replace Verhulst – the man who had come as his lieutenant and who has gone down in history as purchasing Manhattan from the Indians for 24 dollars, Peter Minuit. His takeover wasn’t the last sign of a rebellious streak in Minuit. After the Company recalled him a few years later, he carried out the act Verhulst only threatened. He went to work for the Swedes,

The next Director fared a little better with the people, Wouter van Twiller, who brought Griet as his mistress. Perhaps he was more tolerant of the people’s behavior, given his own, and more interested in snapping up real estate for himself than tending to the Company’s business. He had a particular fondness for islands, taking title to what today are Roosevelt, Randalls, Wards in the Hellgate where Long Island Sound meets the East Rver and Governor’s Island in the bay.

The notorious Willem Kieft succeeded Van Twiller. One of his first acts aimed to straighten out the people’s morals. He issued An Ordinance against Immoderate Drinking. Imbibing too much beer and brandy led to much evil and mischief, Kieft charged. He wouldn’t abide it. Nor would he accept the selling of wine except from official Company stores. Perhaps competition cutting into the Company’s profits was as much concern as the people’s morals.

Kieft went on to outlaw drinking past the 10 p.m. curfew and fornicating with savages. Then he outlawed the festivities of Shrove Tuesday, the day before Lent. New Orleans didn’t hold America’s first Mardi Gras, New York did.

Shrove Tuesday was a day dear to Dutch culture. It began with men stealing the skirts from their wives and parading through the streets – New York’s first transvestites if only for a day. Their wives chased after them bare-bummed.

After the ladies reclaimed their clothing, the celebration proceeded to Pulling the Goose. A goose was buried in the street with its head sticking out and waving like a hydra dodging Hercules’s sword. Men galloped by at full speed, grabbing at the neck. The one who got hold and tore off the goose’s head won a prize.

With the competition over, everyone got back to drinking and brawling with an intensity that led to the Dutch proverb, a hundred Netherlanders, a hundred knives. More Dutchmen landed at the doctor or in the cemetery on Shrove Tuesday than any other day of the year.

All Kieft’s ruining the fun stirred the people of New Amsterdam up to a boil. When Kieft launched a massacre that started an Indian war, they were ready to lynch him. A tailor named Hendrick Kip suggested they send Kieft to Master Gerritt in Amsterdam. Those in the know understood that Master Gerritt referred to the public executioner. Kip offered to send along a pound Flemish so Kieft could die like a nobleman. A pound Flemish would buy a man an axe instead of a rope.

The people didn’t send Kieft to Master Gerritt, they arguably did something bolder. They wrote a letter to the Company, specifically to the Prudent Gentlemen of the Amsterdam Chamber, the committee that handled day to day operations. After outlining the colony’s forlorn condition and Kieft’s crimes, they got to the point: either send us a new governor or we’re packing up our wives and children and quitting the place.

That wasn’t bold enough though. The people also went over the Company’s head and wrote the High and Mighty Lords the States General, the ruling body of the Netherlands. That amounted to appealing to the boss’s bosses’ bosses’ bosses. In the Dutch scheme of things, there wasn’t any higher to go before God.

Sure enough, their High Mightinesses sent a missive down to their Honors the Nineteen who ruled the Company wondering why their lofty heights were being disturbed. And their Honors the Nineteen passed the missive down to the Prudent Gentlemen of the Amsterdam Chamber who handled operations asking how affairs reached such a state that their High Mightninesses were butting into Company business. And the Prudent Gentleman decided they better find a scapegoat, and who fit that bill better than the man on the spot, Director Kieft? Before he knew it, all the colony’s troubles were laid on Kieft’s shoulders.

It took a few years, things moved slowly in those days, but the Company recalled Kieft. The people got what they asked for, a new governor. Unfortunately for them, his name was Peter Stuyvesant, and he was the most effective tyrant the Company had yet sent. He didn’t take long to impose ordinances that made Kieft’s look mild.

First off, he outlawed the pig pens and privies that occupied the streets of New Amsterdam. From now on, he warned the people, keep yourselves and your livestock shitting on your own property. He liked to ride his horse through town and evidently didn’t appreciate the stench or dirtying his horse’s feet.

Then he went after the tavern keepers. Fully one quarter of the town was brandy shops and tobacco and beer houses, he charged. As a consequence, honorable trades were being neglected and the people seriously debauched. Worse still, youth, seeing the improper example of their parents, were being set on a path toward the devil. So all clandestine groggeries were being shut down and any legitimate tippling places better apply for a license.

Furthermore, Stuyvesant ordered, if a tavern keeper sees any fighting or mischief in his establishment, he better inform an officer immediately on pain of forfeiting his business. He’d be fined a pound Flemish for every hour he concealed the matter. And Stuyvesant would no longer tolerate reveling at unseasonable hours or drinking to excess on the Sabbath. From now on, the curfew bell would ring at 9 p.m., and tavern keepers would shut down their taps. Nor would they serve before three in the afternoon on Sundays.

Next, Myn Heer General, as Stuyvesant insisted he be addressed, was sick and tired of how the town profaned the Holy Sabbath. From no on the Dominies would preach both morning and afternoon on Sundays. All officers, subjects and vassals were commanded to attend both sermons. No more tapping, fishing, hunting or any other fun until afternoon services ended.

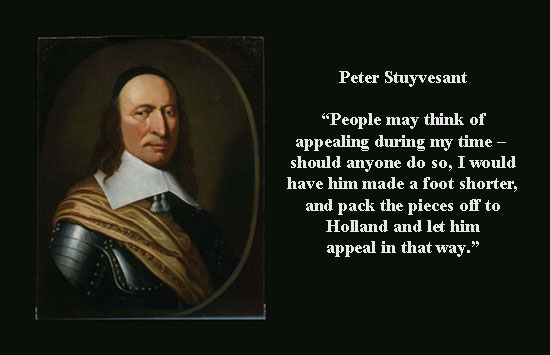

Those orders marked the beginning of a tumultuous relationship that would last seventeen years, until the English took over. In Stuyvesant’s view, the people better obey and keep their mouths’ shut. To speak evil of one’s superiors was one of the greatest offenses a person could commit against the government. Crimen lasae majestatis, Stuvesant called it in Latin. Under military law, a soldier could be punished with loss of limb or life for ridiculing his superiors, he warned. The he quoted canon law: “Whosoever slanders God, the authorities or his parents shall be stoned to death.”

The people protested once again to their High Mightinesses the States General. Stuyvesant warned them again. Anyone who thought of appealing his rulings to Amsterdam would be made a foot shorter and packed off to Holland in pieces, his removed head shipped in its own box. While Stuyvesant never actually chopped off any heads, he did ruin many who questioned his authority, from the richest merchant to the lowliest baker.

Threats notwithstanding, the people persisted. Finally their High Mightinesses listened. They recalled Stuyvesant. But before the ship carrying the order set sail for New Amsterdam, Englishmen fired on another Dutch ship in the channel separating the Netherlands from England. “War,” the Company cried, “we can’t change the government in the colony now.” To the people’s chagrin, their High Mightinesses agreed. They snatched their order back.

While New Amsterdam was stuck with Stuyvesant until the bitter end, the people’s protests finally brought them one victory. In 1653, their High Mightinesses ordered Stuyvesant to stop butting his nose into every petty dispute and allow New Amsterdam to set up its own municipal government – a date some historians consider the birth of New York City.

Stuyvesant’s Amours

STUYVESANT, THE STIFFEST OF MEN who was so outraged by immoral behavior, must have nearly burst in anger when “Broad Advice” was published in 1649. Purporting to offer advice to the West India Company, this pamphlet really delivered a libelous screed against Stuyvesant and his predecessor Director Kieft.

The writer presumably was a sworn enemy named Adriaen van der Donck, who had led a delegation to Amsterdam to demand Stuyvesant’s recall. He knew how to hit Myn Heer General where it hurt. As a young man, Stuyvesant had attended the University of Franeker in Holland. Though he failed to graduate, thereafter he signed his name not Peter but Petrus, the Latin variation because an educated man should have a Latin name.

Why did Stuyvesant fail to graduate? Broad Advice delivered the answer. The son of a Dutch Reformed minister “robbed the daughter of his host,” or in more modern language, he couldn’t keep his hands off his landlord’s daughter or his prick in his pants. The university booted him out for seducing the young virgin.

Arguably the next charge enraged Stuyvesant even more, questioning as it did his service to the Company. Before coming to New Amsterdam, he commanded the Company’s holdings in the Caribbean. With the Netherlands locked in a bitter war with Spain, he attacked the Spanish stronghold at St. Martin. A cannon ball tore his right leg off, forcing the Dutch to retreat.

Why had the Dutch lost the battle? Broad Advice delivered an answer for that question too. The puffed-up peacock Stuyvesant burned all the powder firing salutes to himself on the voyage to St. Martin. None was left to fight the Spaniards. Indeed when the very first ball from the enemy’s cannon shattered his leg, Stuyvesant retreated so fast that the Dutch left everything behind, even their field pieces. After such an heroic action, was it any wonder the Company appointed him to Director in New Amsterdam?

A lost leg would kill a man of lesser steel. But Stuyvesant returned to the Holland home of his sister Anna to recuperate. Judith Bayard, the sister of Anna’s husband, nursed him back to health. At thirty-seven, the nurse was a spinster long past marrying age. Three years younger and no spring chicken himself, Stuyvesant took a shine to Judith.

Stuyvesant told her brother that he intended to ask Judith for her hand. The brother scoffed. “You will never get the nerve,” he claimed, and he would put his money on it. He proposed a bet of a considerable quantity of French wine.

Stuyvesant’s friend John Farret agreed. The two men were so close they wrote poems to one another. Upon hearing of Stuyvesant’s wound, Farret had penned:

My Stuyvesant, who falls and tumbles on his bulwark,

Where, like a dutiful soldier, he taunted the enemy,

To lure him into the field, on the Island of St. Marten.

The bullet hits his leg; the rebound touches my heart.

[Translation by Dr. Elizabeth Paling Funk)

Upon hearing of his friend’s betrothal, Farret chose a different theme for the poem he sent. Priapus has died in you, my friend, he wrote, referring to a Greek fertility God. If wed, you will never consummate the relationship. Stuyvesant was furious. He charged his friend with trying to make him lose the bet of wine.

But Stuyvesant and his bride married before setting sail for New Amsterdam, probably toasting their nuptials with the wine he won. Farret had to eat his words. When the couple stepped onto the Manhattan shore, Stuyvesant was sporting a new wooden leg and Judith was four months pregnant with their first of two sons.

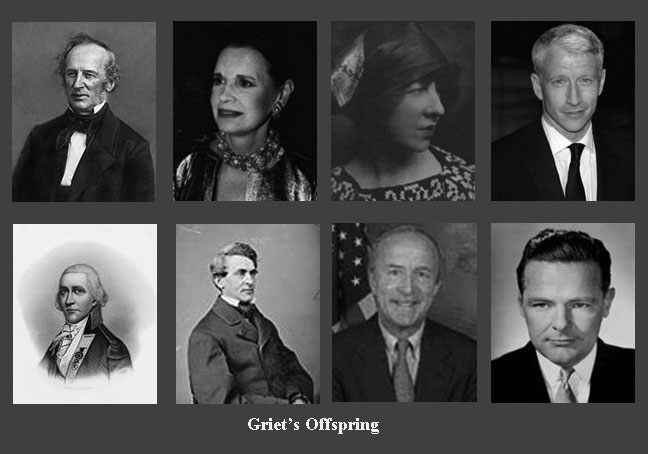

Griet’s Offspring

AS MANHATTAN’S FIRST WOMAN ON THE PROWL, Griet may be the spiritual mother of the Sex and the City girls. But her role as mother extends far beyond television. Five generations down, Griet and the Turk’s descendants married into the clan spawned by another of New York’s earliest couples. Catalina Trico and Joris Rapalje came as newlyweds among the first families the Dutch sent to the Hudson Valley. Catalina bore the first white child, a daughter named Sarah.

The union of these families produced Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt, whose steamboats and railroads made him the richest man of his era. Through the Commodore, Griet was ultimately responsible for fashion designer Gloria Vanderbilt, museum benefactor Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, two Dukes of Marlborough and a host of Lords and Ladies they begat and CNN celebrity Anderson Cooper. Through another of her daughters, Griet led to several senators and congressmen in the Frelinghuysen family, including a current member of the House of Representatives, Rodney Frelinghuysen.

The Public Television news show Frontline has claimed that Griet also has as family a First Lady and a renowned Hollywood actor. It is not absolutely clear whether the claim is that Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis and Humphrey Bogart were great-grandchildren of Griet and the Turk several times over or niece and nephew by way of Anthony’s supposed brother Abraham. Either way, New York’s first whore passed something of herself to the city of today.

Go to: Part 1

Bill's Books

The Mevrouw Who Saved Manhattan

A Novel of New Amsterdam by Bill Greer

A "romp through the history of New Netherland that would surely have Petrus Stuyvesant complaining about the riot transpiring between its pages ... Readers are guaranteed a genuine adventure that will evoke the full range of human emotions. Once begun, they can expect to experience that rare difficulty in putting down a book before they have finished."

-- de Halve Maen, Journal of the Holland Society of New York

About the Book

_________________________

A DIRTY YEAR

Sex, Suffrage & Scandal in Gilded Age New York

A nonfiction narrative of 1872 New York, a city convulsing with social upheaval and sexual revolution and beset with all the excitement and challenges a moment of transformation brings.

From Chicago Review Press, 2020

More on the Book